Julia, The Plain Child

Julia Dent (1826-1902) was the fourth of eight children (one died in infancy) born to Frederick W. Dent and Ellen Bray Wrenshall. Four boys and four girls. In that order. Colonel Dent (an honorary title) was Pennsylvania born, but had migrated to St. Louis, MO as a young man. He became a merchant, bought property, married and raised a family.

Julia Boggs Dent was the eldest daughter. Growing up with four older brothers practically assured a tomboy upbringing, which she readily admitted throughout her life. She rode well, climbed trees, swam, ran races and enjoy the outdoors.

She was also what was usually called, “plain.” She had mousy-colored hair, an average body build that promised stoutness with motherhood and age, along with an eye condition medically called strabismus, more commonly called cross-eyed. While it is routinely corrected in early childhood today, there were no remedies in the 1820s.

Nevertheless, Julia had a warm disposition, and was never at a loss for friends and companions. That included beaux, once she reached the age when beaux were permitted.

The Steady Beaux

When she graduated from finishing school in St. Louis, she returned to her family’s modest plantation outside of town. There she met Second Lt. Ulysses S. Grant, a West Point classmate and good friend of her brother. Grant was assigned to Jefferson Barracks, not far from the Dent home, and called on his friend’s parents as a courtesy. They liked him, insisting that he “not be a stranger.”

The attraction between the 21-year-old Grant and 18-year-old Miss Dent was immediate. Grant was shy with the ladies, but Julia was someone he could talk to easily. He began visiting often to take Julia riding. Or walking, or picnicking, or just sitting on the front porch. Within a few months, he was reassigned – and in love. Reluctant to leave her, he proposed marriage.

The young couple decided to become engaged – in secret. They corresponded and waited for four years, separated by the War with Mexico before the brevet Captain Grant was reunited with his now-22-year-old fiancé.

The Unfashionable Mrs. Grant

With the exception of having “the most beautiful wedding dress I ever saw,” a gift from a family member in St. Louis who was happy to mentor the teenaged Julia and expose her to the best St. Louis had to offer, Julia was never a follower of fashion. She was an Army wife. They moved around.

Two years later, USG was assigned to the California-Oregon territories, and spent two lonely and miserable years that culminated in his resignation in disgrace. Back in St. Louis, the family Grant fell on hard times. For the better part of six years, he could not find work. His efforts in farming were unsuccessful. And with four small children, fashion and style were not part of Julia’s needs. She wore what she already had.

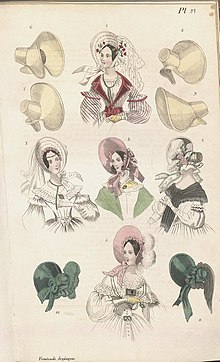

Hats

For centuries, head coverings of some kind were essential to a woman’s wardrobe. In the 19th century, no woman, rich, poor or anywhere in the middle, would think of leaving her home without a hat any more than she would leave without shoes. The styles changed often enough, but the premise was the same. You wore a hat.

In the mid-19th century, “bonnets” became the dominant millinery style for decades. Whether various types of cloth or straw, BONNETS fit snugly around the woman’s head and tied under the chin. It usually featured a brim which framed the wearer’s face. Most women of reasonable means had several bonnets.

Better Times

Only months before Lincoln’s election in 1860, ex-Captain Grant moved with his young family to Galena, IL, to take a clerical position in one of his father’s tanneries. It was a job he had detested from his youth, but he was desperate.

After the fall of Ft. Sumter in April, 1861, the Civil War began in earnest. Trained and experienced army officers were urgently needed. It was no secret in Galena that the tannery clerk was West Point trained and had fought in Mexico. He was the only citizen of Galena with military expertise. He was asked to train the dozens of young men eager to join the army. The ex-Captain agreed to his voluntary role, applied for reinstatement, and (it is said) never set foot in the tannery again.

Reinstated as a Colonel and quickly promoted to Brigadier General, he now had an officer’s pay to support his family.

Julia was instructed to pack up, take the children, and be prepared to go wherever USG directed. He wanted his family close by. For the next four years, according to Julia, “she was Penelope following her Ulysses,” staying with family or friends, in hotels or boarding houses, and frequently in camp with her husband.

The Bad Hat

Early in the war, Mrs. General Grant found herself in need of a new winter bonnet. Accordingly, she and a cousin went shopping in Cincinnati, right on the Ohio-Kentucky border – with a fair percentage of Confederate supporters.

Julia found a charming bonnet. It was nut brown, with red and white rosettes in cut velvet. It was within her budget. She bought it.

But the first time she wore it, she noticed passers-by snickering or staring at her. It made her uncomfortable.

What she didn’t know was that in 1861-2, nut brown with red and white cockades was a tacit symbol for Southern sympathizing women to show their support. Julia was indeed naive, but immediately realized that the wife of a UNION GENERAL could not be seen wearing a bonnet indicating favor to their enemies. Bad. Very bad.

Julia was mortified, and took her shopping companion to task for not advising her of the situation, but was countered with, “but I thought you knew….” They all say that.

Julia never wore that hat again.

Later…

When the Widow Grant was in her seventies, she penned her own memoir. It was never published, and indeed was buried in a trunk in a granddaughter’s attic. It finally was discovered and published – in 1975 – nearly 75 years after her death. She told this “embarrassing story” in that memoir.

She did not have to tell it. It happened some 35 years after it occurred. Nobody would have known. Or cared. That she opted to do so is very telling about Julia. She was confident enough in her own self to allow her oops moment to be made public. And you like her all the better for it.

Sources:

Foster, Feather Schwartz – Mary Lincoln’s Flannel Pajamas and Other Stories from the First Ladies’ Closet – Koehler Publishing, 2016

Grant, Julia Dent, (Simon, John Y. Ed.) – The Personal Memoirs of Julia Dent Grant – G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1975

Ross, Ishbel – The General’s Wife – Dodd, Mead, 1959

Amusing story . Thanks for the chuckles . My mom loves to wear fashionable hats too , especially to church on Sundays