The Procession

As far back as recorded time goes, when a Great War was over, the victors paraded through their towns and villages, trumpets blaring. Hundreds, and even thousands of soldiers glittered in their armor, assembled and proud.

Most marched. The leaders rode on horseback. In some cultures, kings and princes rode in horse-drawn wagons or chariots, decked out in all their glory. Some rode on elephants. Wagons followed in the parade, filled with the spoils of war: gold and silver, jewels, the finery and opulence of wealth and power now in possession of others.

Toward the end of the procession, were the vanquished. Men, women and children, including the ill and frail, often shackled together, to be distributed as slaves – to the victorious. And the crowds cheered. Occasionally great arches were built to commemorate the great victory.

The parades were repeated over and over throughout millenniums. Some of the arches still stand.

April 2, 1865

Confederate President Jefferson Davis had received the news he had been dreading for weeks. General Robert E. Lee had advised him that his disintegrating army could no longer withstand the long siege in Petersburg, nor protect the Confederate Capital in Richmond, just across the River. He advised the President to evacuate.

It was not a surprise to Davis, a former West Point officer himself. The department heads of the remaining Confederate government had already packed up their records and paperwork and loaded it onto waiting trains.

When all was done, strategic fires were set to deny any goods, services, arms, ammunition – and even shelter, to their enemy.

April 4, 1865

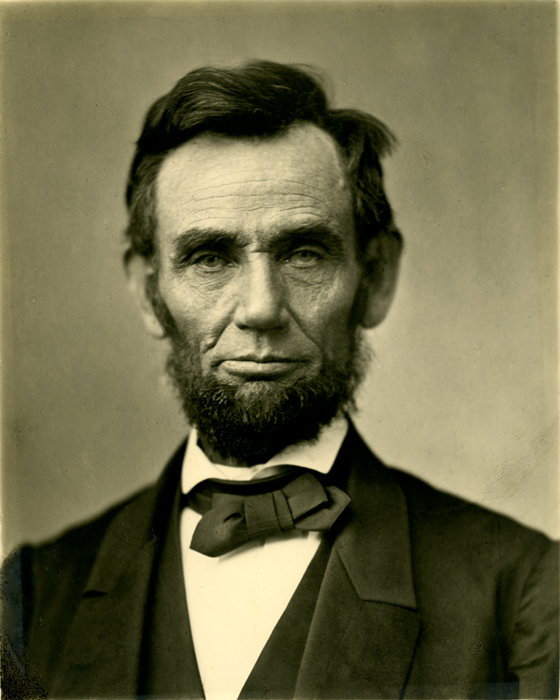

President Abraham Lincoln, tired, underweight and visibly aged from the stresses of four years of a country at war with itself, had arrived two weeks earlier at City Point, VA, at the confluence of the James and Appomattox Rivers, not far from the besieged Petersburg. Said to be the tenth largest city in the Union at the time, City Point had been thrown together some months earlier to supply and support the huge Army of the Potomac, which was now in the throes of mopping up the remainder of the Civil War.

Everyone knew it was only a matter of time before it would finally be over and the killing stopped, and perhaps, the healing could begin.

Spring had come early that year in Washington, some hundred miles away. The President and his family decided to “visit the army” at the invitation of General Ulysses S. Grant. They sailed down the Potomac aboard the River Queen, into the Chesapeake Bay, and finally up the mighty James River.

He had already spent nearly two weeks with the Army, reviewed their parades, met with their commanders, and greeted the rank and file, something he always enjoyed. The soldiers had grown to love and respect him, and it is said, it was their that ballots guaranteed his second term. Lincoln had also met the USCT (United States Colored Troops, as they were then called), who revered him as their savior. AL was sincere in his recognition of their valor and contribution, and was visibly touched by his reception.

General Grant had already amassed his vast army and began chasing the exhausted Rebels through central Virginia.

It was a rarity. The President had a free day.

Richmond

“I have always wanted to see Richmond,” Lincoln is said to have commented. So with his eleven-year-old son Tad, Admiral David Porter, and a handful of military escorts, the President boarded one of the riverboats, and sailed the short distance to Richmond. The smell of smoke and ash from its self-inflicted fires permeated the air, as a barge rowed him and his party ashore.

Nobody knew he was coming. That included a skeletal Union Army dispatched to maintain order. Of course the tall, lanky President, made a foot taller in his stovepipe hat, was visible. If he had any thought or fear that he might be a target for a well-placed sniper, it is unknown. If he thought his appearance was an act of heroism, it is also unknown.

But immediately after stepping ashore, he was recognized by some of the Negroes, and according to Admiral Porter, “No electric wire could have carried the news faster.” Within minutes, the President was surrounded by throngs of Negroes and whites alike, eager to touch him – or his clothing. Or shake his hand.

It was perhaps a mile from the river to the Confederate “White House,” – a mostly uphill walk. It was also a particularly warm day, and Lincoln was perspiring heavily. He moved slowly, since he was completely surrounded by hundreds of men, women and even children. When some Negroes knelt in his path, Lincoln was embarrassed, saying they should kneel only to God.

When he finally entered the Confederate White House, which in essence was a comfortable city-mansion, he was taken to Jefferson Davis’ office, and sat in his chair. When asked by his escort if they could get anything for him, he asked for “a glass of water.” He was hot and tired. And emotionally drained. The past four years were catching up with him. People remarked how much he had aged. He likely agreed. It hadn’t been easy.

One cannot fathom what went on in Abraham Lincoln’s mind while he sat at Davis’ desk. The ghosts of a hundred thousand – or more – Americans North and South who had given their lives in the War, could not have been too far from his thoughts. They never were.

While he was in still in Richmond, he received a wire from Secretary of War Stanton. Secretary of State William Seward had been seriously injured in a carriage accident. His little respite was over.

It was time to go back to Washington.

Sources:

Foote, Shelby – The Civil War: A Narrative: Volume 3: Red River to Appomattox – Vintage Book, 1986

Kelly, C. Brian – Best Little Stories from the Civil War: More than 100 true stories – Cumberland Press, 2010

Searcher, Victor – The Farewell to Lincoln – Abington Press, 1965