A quarter century after James Monroe died, he was buried. Again.

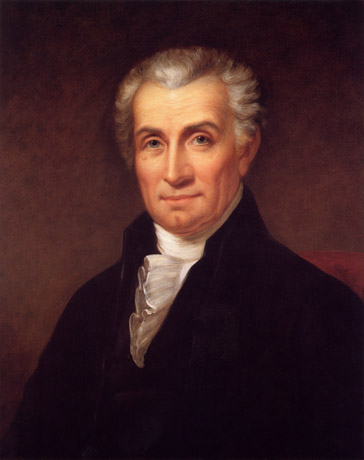

James Monroe, Virginian

Like his close friends and Revolutionary companions Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, James Monroe (1758-1831) had strong ties to Virginia. Monroe could arguably considered the one with the tightest tie to the Old Dominion, having served in its state government in numerous positions, from legislator to state senator, and its Governor. Twice.

Then, of course, he was the fifth President of the United States, and part of what was termed the Virginia Triumvirate: Jefferson, Madison and Monroe, serving consecutively for two terms each, covering more than two decades of US leadership.

When he retired from the Presidency in 1825 he was 66, and still in generally good health. His wife, ten years his junior, was becoming frail. Nevertheless, they returned to Oak Hill, their home about 35 miles from Washington. As might be expected, he served on the Board of Visitors for Jefferson’s newly established University of Virginia.

His ties to the state were strong.

Those Last Years

For the better part of five years, Monroe enjoyed his retirement life of “gentleman planter” much like his fellow Virginia Presidents. Also, like his predecessors, Monroe, who had never been wealthy, had incurred several debts throughout his life, and now battled insolvency. He sold his Ash Lawn plantation (close to Monticello) which today is open and managed by the College of William and Mary.

He remained active, serving as a delegate to the Virginia Constitutional Convention in 1829, but forced to relinquish his role as its presiding officer in 1830, due to failing health.

It was death of his wife Elizabeth Kortright (1768-1830) that helped precipitate his decline. They had been married more than 40 years, during which time they had seldom been apart for more than brief periods. Even during the two decades (on and off) that Monroe served abroad in ambassadorial positions, Elizabeth was with him.

When she died in 1830, a frail and now-failing James Monroe moved to New York City, to live with his daughter Maria Hester, her husband Samuel Gouverneur and their family. In another historical coincidence, on July 4, 1831 – fifty-five years after the Declaration of Independence was signed – James Monroe died of heart failure, and possibly complications from tuberculosis. He was 73.

His family buried him at a simple ceremony in the Gouverneur family vault at Marble Hill Cemetery in New York. There were no Virginians present. He would lay there for more than a quarter century.

Hollywood: The Cemetery

Cemeteries, including important ones, have been around for millennia. The Egyptians had their pyramids, the Romans their catacombs. Various native tribes had their sacred burial grounds. Once European colonists began to populate the American continent, crypts and cemeteries were usually attached to churches. Many people however, preferred interment on their own property, a la George Washington. Several “modern” presidents choose burial at their associated institutions.

In 1847, a sprawling “garden cemetery” was built in Richmond, VA, near the banks of the James River. Unlike the grid-like cemeteries, this one, sprawled on 135 acres of valleys, hills and stately trees was a new concept of the 19th century that became very popular. They called it Hollywood Cemetery, and today it is recognized as a registered arboretum.

During the next decade, the beautiful cemetery (one of Richmond’s treasures) was growing in “residents” and status. By the mid-1850s, as sectionalism and secession between North and South were creating huge rifts, its Governor Henry A. Wise wanted to make a statement, ostensibly seeking our dear departed Founding Fathers of Virginia to provide a more moderate tone and remembrance.

George Washington being removed from Mount Vernon was out of the question, of course, but both Jefferson’s Monticello and Madison’s Montpelier had been sold and were falling into disrepair. No close family ties remained there. Gov. Wise had hoped to bring the coffins of both Jefferson and Madison (two of Virginia’s favorite sons) to be re-interred at Hollywood, but for various reasons (and perhaps historical serendipity), those efforts failed.

Monroe was a different story, however. He had no ties to New York. Why shouldn’t his earthly remains “come home”? His son-in-law, still living, had no objection.

The Homecoming

So on July 2, 1858, 100 years after James Monroe’s birth, with $2000 authorized by Virginia’s General Assembly, “officials from Virginia and New York joined descendants of Monroe at the cemetery in New York to see the lead coffin dug up and placed in a mahogany casket.”

The following day it was placed on a steamship, appropriately named Jamestown, and brought from New York, through the Chesapeake Bay, and up the James River to Hollywood Cemetery. “On the night of July 4-5, a crowd of Richmonders assembled at the dock for their arrival. Then Gov. Wise and Richmond Mayor Joseph Mayo led the funeral procession through Richmond’s streets to the cemetery, two miles away. Monroe’s coffin was borne in a hearse drawn by six white horses.”

The ceremony was held with a limited number of spectators (not enough room) followed by some gala celebrations in town. Newspapers across the country reported the event, and the desire to “re-unite” the country.

His wife, daughter and son-in-law have been re-buried nearby.

The Birdcage – Hollywood Style

In 1859, Albert Lybrock, an Alsatian architect who emigrated to the USA some years earlier, designed a beautiful and ornate Gothic Revival cage made from cast iron, which surrounds the sarcophagus. It has been nicknamed “The Birdcage”.

It was labeled a National Historic Landmark by the National Park Service in 1971 due to its unique and elegant architecture.

In 2015, the State of Virginia appropriated nearly $1 million to repair the structure, and return it to its original beauty.

Sources:

Cresson, W.P. – James Monroe – UNC Press, 1946

Unger, Harlow Giles – The Last Founding Father – DeCapo Press, 2009

https://www.britannica.com/biography/James-Monroe

https://www.hollywoodcemetery.org/

https://www.dailypress.com/news/dp-xpm-19940904-1994-09-04-9409020413-story.html

Reblogged this on Dave Loves History.

Reblogged this on Practically Historical.