The similarities were apparent; the dissimilarities were intrinsic.

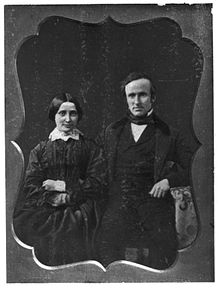

Mary Todd Lincoln (1818-1883) was seven years older than Julia Dent Grant. From Kentucky and Missouri respectively, they were both considered “westerners” in the early part of the 19th century. They both grew up in large families. Both families were affluent enough (Mary more so), and were slave holders. They were both finishing-school educated.

But Mary’s childhood was desolate, according to her. She was the 4th of 6 children born to Kentucky banker-legislator Robert Smith Todd and his first wife. He owned a house in town plus and a plantation outside Lexington. When Eliza Todd died in childbirth, her widowed husband, perhaps overwhelmed by six children under twelve, remarried 18 months later. Betsey Humphreys was a strict, remote woman by nature, who nevertheless produced eight more little Todds.

Mary and her full-siblings were overlooked, neglected and criticized. They could not wait to escape. Mary, arguably the most intellectually inclined, went to finishing school when she was around twelve. Even though the school was only a mile from their town house, Mary boarded during the week, returning only on the weekends.

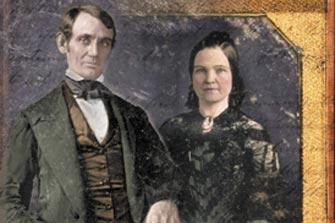

When her older sister married, moved to Springfield IL, and sent for her full-sisters, Mary jumped at the opportunity. She was just shy of 24 when she married Abraham Lincoln, ten years her senior. And poor.

The Diva Grant

Julia Dent (1826-1902) was the 4th of eight: four boys and four girls in that order. (One daughter died in infancy). Her father Frederick Dent was a merchant and plantation owner in St. Louis MO, a bustling port city. They had a house in town for the winter.

But Julia’s childhood was a loving one, with memories, according to her memoirs written in her elder years that glowed brighter every year. But she was a plain child, with an eye condition from birth. Today, people call it cross-eyed, easily and successfully corrected in infancy. In the 1820s, it could not be repaired.

She was petted and spoiled by her parents and brothers but was blessed with a warm and affectionate personality that always won her many friends. Because her eye condition produced understandable eyestrain and headaches, she was permitted to be relaxed in her academic achievements. In the nineteenth century, education for women was never essential. And Julia would never be a scholar. Or pretty.

She met a recent West Point graduate, her brother’s academy roommate, when she was barely 18 and he 21. It was love at first sight, but their marriage did not take place for four years, punctuated by his military obligations, youth and financial strains.

The Mary Surprise

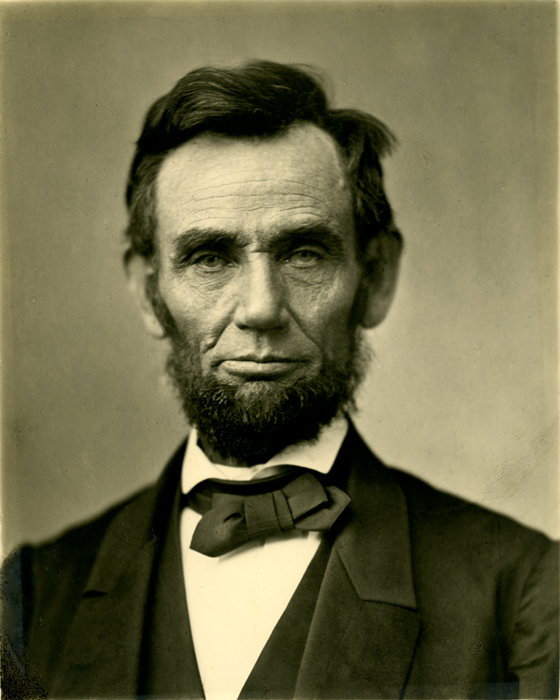

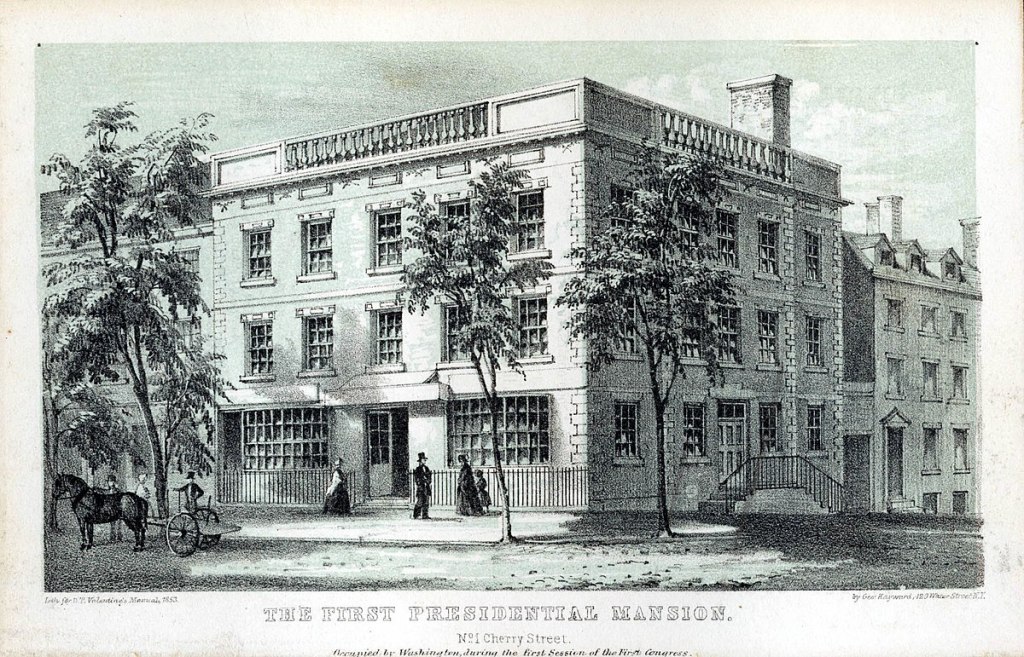

For 18 years, Mary Lincoln had been a middle-class housewife in Springfield, the capital of Illinois. It was a successful enough union, despite a decade of single-parenting while AL rode the judicial circuit to earn his modest living. His rise in politics was a long haul, but by 1860, he had reached national attention in the new Republican Party and became its Presidential nominee. A Civil War loomed on the horizon. When he was elected, war became a foregone conclusion.

When the Lincolns arrived in Washington a few weeks prior to the inauguration, Mary was traumatically blindsided. She had three strikes against her from the start that she did not expect. First, while most people knew that AL came from humble roots, they assumed Mrs. Lincoln was also from that social class. She was not – by a longshot. Secondly, she was also a Kentuckian from a slave holding family, and thus perceived to be a Southern sympathizer. True about the Kentucky-slave holding part, but Mary was opposed to slavery since childhood, and was devoted to the Union. And third, as a “westerner,” she was purported to be of “low taste.” Untrue. Mary was particularly well educated and believed herself to be equal to her upcoming social tasks.

When a delegation of Congressional wives came to call on the FLOTUS-elect, they offered to “guide her” through the shoals of society. They likely were a little condescending, but they meant well. Mary was offended and let them know it. In its own way, she was traumatized, and her sense of “I’ll show them,” began to take root. She would insist on the best, and would tolerate no peers.

They shunned her.

The Julia Surprise

While Julia Grant always loved and believed in her husband, Ex-Captain Ulysses S. Grant was a sad case for the first fifteen years of their marriage. His military career ostensibly ended, and his attempts to find suitable work in St. Louis non-existent, the Grants barely got by. He finally wound up as a clerk in one of his father’s tanneries in Galena IL, a position he hated. But USG was not an ambitious man past providing for his family.

When the Civil War began in 1861, Grant’s military career was resuscitated, and his rise, while not meteoric, was steady – and at a high level. Within a year, he was a Brigadier General with solid success on the battlefield.

By early spring 1864, President Lincoln had finally found his man and promoted him Lt. General of the Army – top dog. All of a sudden, Mrs. General Grant, was becoming a person of interest.

Meeting of the Divas

USG, honored in a modest White House ceremony, had sent for his wife to witness the occasion, and to find suitable housing. She was introduced to the President, who invited her to one of Mrs. Lincoln’s receptions a few days later. Of course she went! Lincoln recognized her, and personally introduced her to the First Lady. They smiled, shook hands and murmured the usual “glad to meet you.”

That was it – for about a year. Meanwhile, the Congressional wives who snubbed/were snubbed by the First Lady, descended upon Mrs. Grant, and made her the same offer: help her through the shoals of society. Perhaps knowing that she probably could use the help, Julia Grant, true to her plain image and pleasant unassuming nature, said thank-you-very-much.

They loved her.

Sources:

Clinton, Catherine – Mrs. Lincoln: A Life – Harper Collins, 2009

Grant, Julia Dent – The Personal Memoirs of Julia Dent Grant: (Mrs. Ulysses S. Grant) – 1975, G.P. Putnam’s Sons

Helm, Katherine – MARY: Wife of Lincoln – Harper and Brothers – 1928

Ross, Ishbel – The General’s Wife – Dodd, Mead, 1959

https://www.mtlhouse.org/biography

https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/first-families/julia-dent-grant