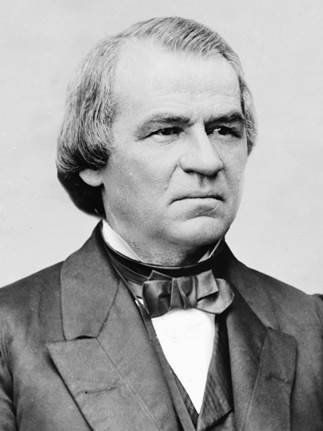

Andrew Johnson is one of the most unlikely US Presidents

The Unlikely POTUS

Beginning with Andrew Jackson in 1828, and into the 20th century, the White House was the home of some of the most unlikely men who ever rose to the office of President.

With rare exception, they came from undistinguished families; certainly far from wealthy, and in several cases, downright poor. Most of them had limited resources other than their own natural abilities and talents – and an intense desire to better their lot. And luck.

Andrew Johnson (1808-1875) would arguably be at the bottom of the barrel in a list of unlikely-undistinguished. His parents were uneducated menial servants in a tavern. His father died when Andrew was two. His mother remarried a man just as poor and uneducated as her first husband. In his youth, Andrew and his older brother were apprenticed out to a tailor as a kindness: it would provide the boys with food and lodging, and the opportunity to learn a trade to make their own ways in the world.

Andrew did become a tailor, considered a fine craftsman. He married at eighteen, opened a shop in working-class Greenville TN, made men’s suits and coats, and with his wife’s help, learned to read, write and cipher. By his early twenties, he attended town meetings and rose quickly in local politics. He remained in public life for the next 35 years.

Andrew Johnson had done very well for such an impoverished beginning.

Andrew Johnson: The Civil War

By the onset of the Civil War in 1861, Andrew Johnson had been in Congress for nearly two decades. He was well known in its small universe of politicians. But while his peers acknowledged his daunting circumstances, he had few close friends. His personality was truculent and suspicious: more inclined to fight it out than to compromise and solve problems.

Nevertheless, as the only Senator who did not resign his seat when his state seceded, he provided yeoman service to President Abraham Lincoln during his first term. Eventually AJ was appointed Military Governor of Tennessee, a position challenged by serious physical danger to himself and his family.

Those efforts led to his nomination as Vice President in 1864. The war had gone so badly for the Union, that the Republican Party used a nom de guerre, and called itself the Union party. Lincoln personally wanted Johnson. A repatriated Tennessee was important; ever loyal little Maine (home of VP Hannibal Hamlin) was expendable.

Unfortunately for Andrew Johnson, his inauguration as VP was tainted. He had been ill and left a sick bed to come to the inaugural. The doctor, suspecting typhoid, had prescribed strong whiskey to avert chill, and the outcome became a scandal….

April 14-15, 1865

Andrew Johnson, Vice President for about six weeks, had taken up solitary residence at the Kirkwood House in Washington. His invalid wife and 11-year-old son had not yet moved to the capital.

At 11 p.m. the night of Friday, April 14, Johnson was in bed in his rooms, awakened by a loud banging on his door. When the sleepy VP opened the door, he saw Leonard J. Farwell, the former Governor of Wisconsin and personal friend of Johnson. He was visibly agitated as he blurted out the news he had just heard: President Lincoln had been shot in Ford’s Theater, and was fighting for his life.

Within the hour, Johnson had dressed. Soldiers to guard the VP had arrived, and they made their way over to the Peterson House where the dying Lincoln had been taken. He paid his brief respects to the various dignitaries who attended the vigil. Realizing that his presence was pointless, and perhaps easily misconstrued, he returned to his hotel.

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton had quietly informed him of the sketchy events that had taken place just hours earlier, indicating a conspiracy of some kind. Secretary of State William Seward had also been violently attacked and was near death.

At that point however, there had been no substantial indication that VP Andrew Johnson himself had been targeted for assassination in his rooms at the Kirkwood House. That would come within hours.

By 8 a.m. Johnson received a note from Attorney General James Speed and signed by all the cabinet members (except the wounded Secretary of State Seward) informing him of Lincoln’s death, urging that he take the oath of office as soon as possible. Andrew Johnson agreed: 11 o’clock that morning at the Kirkwood House.

I, Andrew Johnson….

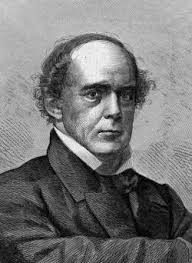

Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase (former Secretary of the Treasury) was summoned to administer the oath.

Joining him to witness the traumatic and monumental event was a small group of notables. Treasury Secretary Hugh McCullough, Attorney General James Speed, Francis P. Blair, Montgomery Blair, Sen. Solomon Foot (VT), Sen. Richard Yates (IL), Sen. Alexander Ramsey (MN), Sen. Wm. Morris Stewart (NV), and Sen. John P. Hale (NH).

The ceremony, performed by the Chief Justice and the new President, was administered quickly, and Andrew Johnson made a brief speech. In it, he remarked, “…The best energies of my life have been spent in endeavoring to establish and perpetuate the principles of free government…The duties have been mine — the consequences are God’s. This has been the foundation of my political creed….”

Following solemn handshakes and sincere well wishing, the group departed. No fanfare. No parades. No banquets. Just overwhelming sorrow.

Sources:

Pitch, Anthony K. – “They Have Killed Papa Dead!”: The Road to Ford’s Theatre, Abraham Lincoln’s Murder, and the Rage for Vengeance: Steerforth, 2009

Trefousse, Hans L. – Andrew Johnson: A Biography – W.W. Norton, 1989

Hotels and Other Public Buildings: Kirkwood House

Reblogged this on .