By the time of Lincoln’s death, his reputation for compassion had become legendary.

Captain Abe

When Abraham Lincoln was around 22, living in New Salem, IL, he enlisted in the militia along with a bunch of his buddies. A skirmish known as the Black Hawk War had erupted in the region, and volunteers were needed. Thus the New Salem fellows signed up, perhaps for larks or an escape from their humdrum farming chores.

As it was, they saw no action, saw no enemy and fired no shots other than for target practice. Mostly it was a month-long camp-out with marching drills. Lincoln, to his great pleasure, was elected by his peers to serve as the captain of their unit. He would later call that election the most gratifying to him.

Summing up his “military experience,” there was none to speak of. He spent the next thirty years as a civilian.

Lincoln: Commander-in-Chief

Suffice it to say, that when Abraham Lincoln became President in 1861, his knowledge of the military was minuscule. He needed to rely on the professionally trained officers who knew about such matters. He was particularly respectful of the aging General Winfield Scott – who had been the commanding general during the long-forgotten Black Hawk War.

One thing Lincoln did know about the military, civilian or not, was that military power (army, navy, marines, etc.) is essential to any nation. He also knew that said military has a plethora of rules, regulations, officers, orders, orders and more orders. By and large, it is necessary, and President Lincoln, as Commander-in-Chief of the US Military, respected that need. Without sufficient (and enforceable) discipline and order, an Army will quickly fall apart.

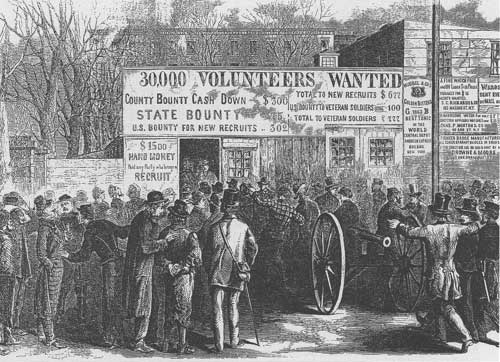

But as Southern States seceded, and shots were fired at Fort Sumter, and the Civil War began in earnest, things changed. The tiny US Army consisted of perhaps 15,000 men and 1500 officers – and a call for 75,000 volunteers was quickly raised and exceeded.

One of the Problems

Most of the new volunteers had no military training past shooting at tin cans on a fence or varmints in their fields. Most of them were farm boys, backwoods men, clerks and otherwise entry-level recruits. And while a high percentage of them could read and write, some didn’t know their left and right. And a very high percentage of them had never been more than a few miles from their homes.

Naturally, the educated recruits, the professionals, the businessmen, the “older guys” and the politicians were the stuff of officers. President Lincoln signed hundreds of military appointments for colonels and generals. He was not a fool, and realized that while many of them made fine officers, a lot of them were bumbling and pontificating mini-autocrats.

When some eighty thousand new recruits enlisted, armed, trained and sent into the field after only a month, there were bound to be problems. If rules and regulations were disobeyed or deliberately flaunted, the punishment could be draconian, if not deadly.

Lincoln-the-compassionate was a practical man, however. If a soldier deserted, or bounty-jumped to reenlist elsewhere (for the money), or encouraged mutiny, etc., he obviously deserved punishment, however severe. But an exhausted young soldier sleeping on sentinel duty, or scared and running to hide, or similar situations was a different story.

High-level commanding officers regularly complained that the President was undermining their discipline.

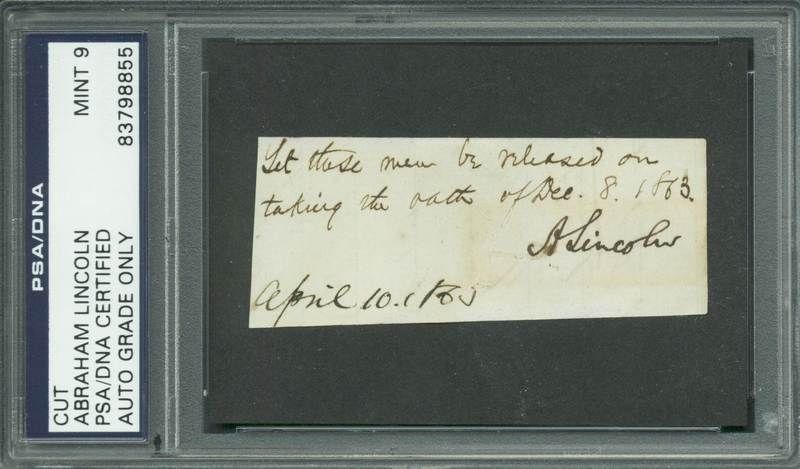

Lincoln insisted on his own latitude. As time went on, he ordered that he personally had to sign off on any court martial for the death sentence.

The Case of William Scott

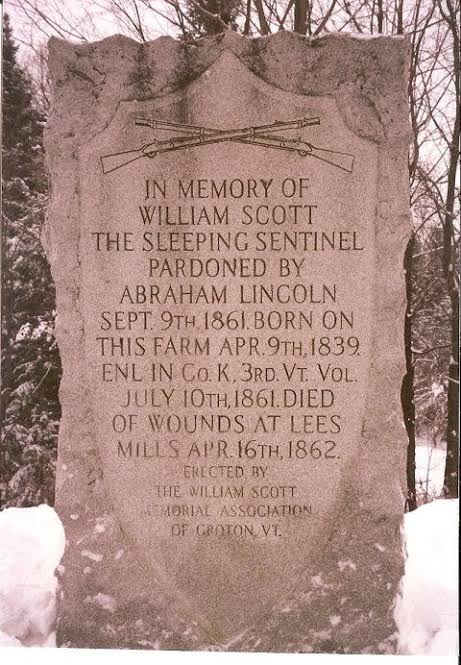

William Scott, was a private in Company K of the Third Vermont Volunteers. He had enlisted right off, and had seen action at the First Battle of Bull Run. They, like the others, had fallen back to Washington in disarray, and the husky young Scott was detailed for night-time sentry duty on the bridge across the Potomac, between Maryland and Virginia (enemy territory)!

They had fought all day, and then had marched miles to their current position, exhausted and demoralized. Young Pvt. Scott nodded off while on watch. He was caught by the Duty Officer, court-martialed and sentenced to death.

Private Scott’s comrades were horrified at the severity of the punishment, and managed to have his case put before the President, who was equally horrified. He pardoned the young private, and had him sent back to his unit.

The story quickly made rounds in the newspapers and magazines, and puffed and embellished via poems and songs, and Private Scott was now “The Sleeping Sentinel,” and in his day, became the best-known Private in the Union Army.

The Sad, Sad End

Less than a year later, General George McClellan initiated a mammoth military campaign in Virginia. On one of the first Union assaults of that effort, Private William Scott received his red badge of courage: six bullets to his body. His fellow soldiers dragged him to safety, where he expired. He was 23.

Francis de Hayes Janvier was an American poet of modest renown, and well skilled in the Victorian sentimentality of his time. He wrote the poem “The Sleeping Sentinel,” commemorating young Pvt. Scott being pardoned by the President just as he was lined up before the firing squad. (That part was an exaggeration). The poem was so poignant, it was read to President and Mrs. Lincoln at a White House reception in early 1863.

The poem was published throughout the North, and even reprinted for many years afterwards. In the nineteen-teens, as moving pictures grew in popularity, a short film, “The Sleeping Sentinel” was based on that poem.

… And, in the last expiring breath, a prayer to Heaven he sent

That God, with his unfailing grace, would bless our president.

Even today, Pvt. William Scott is honored in Vermont.

Sources:

Searcher, Victor – The Farewell to Lincoln – Abington Press, 1965

https://acws.co.uk/archives-military-discipline

He was such a good man and president!