Two Southern legislators, poles apart, bitter enemies.

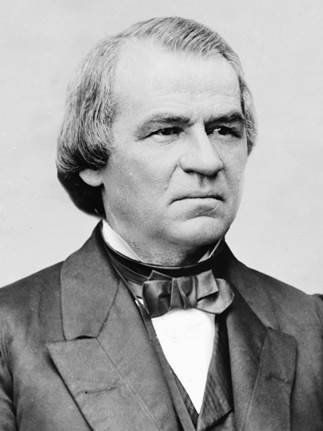

Andrew Johnson: Mechanic

Andrew Johnson (1808-1875) was arguably the poorest of our Presidents, measured in family position (low) and wealth (even lower). His father, a porter for a small tavern-hotel in Raleigh NC, died when AJ was two. His mother, a maid at the same tavern-hotel, remarried a short time later to a man in even poorer circumstances.

When Johnson was around ten, his parents apprenticed him to a tailor. It was a kindness. He would be housed and fed, taught a trade, and perhaps, a bit of schooling. Truculent by nature, Andy proved a difficult apprentice. The master-tailor was said to be stern and difficult as well. Likely enough faults to go around. At seventeen, AJ ran off over the state line to TN, where apprentice laws were not valid.

He arrived in Greeneville with little more than the clothes on his back, but within two or three years, had made a go of it. He married, opened his own shop, and with the help of his wife improved what little 3-R lessons he had learned. He did well enough to become politically active in town. Then he was elected to state office, and then to Congress.

But he never forgot where he came from, or the distance to where he arrived. Or that as a “mechanic,” a term used then for the working class, his bitterest enmity was to the “property” class.

Jefferson Davis: Patrician

There is little similarity between Johnson and Jefferson Davis, except for their closeness in age (1808-89), that they were born in the South, and were basically states’ rights Democrats. Davis’ family were Kentuckians of middle class means. Enough to send their youngest son (JD) to Transylvania College, and then to West Point.

Following his education, Davis served as a junior officer in the US Army, and after completing his service commitments, he resigned to become a planter in Mississippi. He not only did very well, but was elected to public office: the United States Congress.

He was, essentially, a southern gentleman. And never forgot it.

Dem’s Fightin’ Words

It was not slavery that caused the argument. It had to do with the military. Early in their careers, when both men were freshmen Congressmen, the War With Mexico had just begun. There had been a speech criticizing military science and training, with the objective to cut funding, downsize the army and eliminate West Point. As a former West Pointer and soldier, Davis staunchly defended the military, stating that “Arms, like every occupation, requires to be studied before it can be understood.” Davis asked them to consider if a “blacksmith or a tailor could have secured the same results” as General Zachary Taylor’s troops. He had praised Taylor, defended his profession and endeavored to protect future military appropriations.

But it was a red flag to a bull to angry Congressman Andrew Johnson, who perceived the remarks to be demeaning to blacksmiths and tailors. Johnson was insulted and reminded the House that Jesus Christ was the son of a carpenter and Adam a tailor who sewed fig leaves together. This “invidious distinction” Johnson railed, came from the “illegitimate swaggering, bastard, scrub aristocracy” of which Davis was both member and spokesman.

Congressman Jefferson Davis had many faults, but lack of manners was not on the list. He was an unfailingly polite man, and his defense of the military was never intended to be offensive. He apologized immediately. And profusely. Congressman Johnson would have none of it. He had come from nothing, and was proud of his accomplishments. And he always believed that the southern “property” class was most responsible for slavery.

Not that he was without racial bias himself… His basic attitude was that slavery, i.e. free labor, took jobs away from deserving “others.” He believed everyone should be paid wages, and the cream would rise to the top.

Later…

Congressman Davis resigned his Congressional seat to be come a Colonel of Mississippi Volunteers in the War with Mexico, served ably, was wounded severely, returned home to recuperate, and became Secretary of War under President Franklin Pierce.

Andrew Johnson served as Congressman, then Governor of Tennessee, and was finally elected to the U.S. Senate where he served commendably as an unflagging supporter of the Union.

By 1857, both men were U.S. Senators. Johnson had made a solid name for himself as a Unionist, completely opposed to secession, which had been rearing its ugly head for nearly a decade. Davis was now considered the titular leader of the South – despite the fact that he deplored secession.

The relationship between the two Senators was guarded. Davis as always, chilly and polite, and Johnson as always, glowering. Nothing was forgotten. Or forgiven.

Even Later…in 1865

Secession having happened, a Civil War having happened, Davis as Confederate President and Johnson as the only Southern Senator to remain in his seat having happened, Johnson elected Vice President, the war lost, and Lincoln assassinated having happened…

Jefferson Davis was a hunted man, trying perhaps to consolidate remnants of his beaten army, or perhaps to escape the country. He only learned of Lincoln’s assassination a week after it had occurred. He was now positive that he would be hanged for treason. After all, Andrew Johnson, his long-time enemy, was now President. One story said he even remarked to a friend that he would have preferred to take his chances with the kind-hearted Lincoln than the bitter Johnson.

Interestingly enough, Andrew Johnson was kind to ex-CSA First Lady Varina Davis when she went to the White House to plead for her husband. He said his hands were tied. Nevertheless, he let the issue of what to do with Jefferson Davis lie and die.

Sources:

Johnson, Clint – PURSUIT: The Chase, Capture, Persecution and Surprising Release of Confederate President Jefferson Davis – Citadel Press, 2008

Means, Howard – The Avenger Takes His Place – Harcourt, Inc. – 2006

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Andrew-Johnson

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/jefferson-davis