The Admirable Admiral

George Dewey (1837-1917) was a Vermont man, from a prominent family. He was sent to Norwich University when he was fifteen, and expelled two years later for disciplinary matters, perhaps not uncommon for 15-year-olds. He then was enrolled at a fairly-new Naval Academy at Annapolis, and fared very well.

When he graduated in 1858, he was assigned as executive lieutenant on the USS Mississippi, and as the Civil War began and raged, Dewey served under Admiral David Farragut. By the war’s end, had been promoted to Lt. Commander.

For the next 30 years, he commanded several ships, including “Old Ironsides,” served as an instructor at the Naval Academy, and held various other high level naval posts.

By 1897, and now a Commodore approaching retirement age, the always aggressive Dewey was put in charge of the Asiatic Squadron. It was a plum post, given in no small part by political effort from the assistant Secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt – a man young enough to be his son.

In 1897, events in Cuba, only 90 miles from the US mainland, were reaching a crisis. Cuba was part of the Spanish Empire, and the overlords were considered oppressive to the Cubans, who wanted their independence. While most Americans preferred a hands-off policy with their neighbors, a growing sympathy for freedom lovers was quickly emerging.

Dispatching Dewey to the Far East was an important move. The jewel of the Spanish Empire was the Philippines. With orders to be vigilant and prepared, Dewey quietly purchased a ship (under private registration) as a supply vessel, and purchased large quantities of coal and other necessities – just in case.

The “in case” came to pass when war between Spain and the USA was declared, and on May 1, 1898, Commodore Dewey sailed into Manila Harbor at dawn, and sank the Spanish fleet. No American sailors were lost.

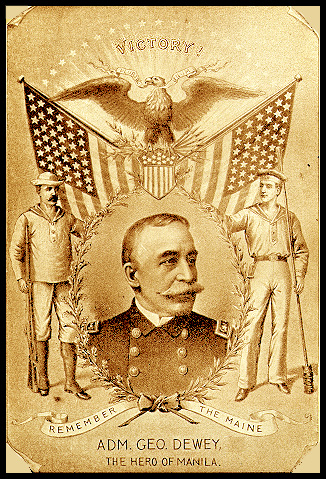

Dewey, quickly promoted to Rear Admiral, was a bona fide hero.

The Trappings of a Hero

When he returned to the US in 1899, there hadn’t been a real hero for decades – and certainly not a real NAVAL hero. The entire country went wild for the new Admiral.

The hoopla was somewhat of a surprise to him. Admiral Dewey was definitely an aggressive officer who knew his duty and his duties, but like General Grant, he was also a basically modest man.

Parades down the main thoroughfares in all the big cities was new to him. But he got used to it, and tipped his hat and waved to the crowds.

He was sincerely touched by the banquets in his honor, the presentation trays and swords and silver stuff. A grateful nation also presented him with an opulent house in Washington DC. He was happy to say thank you.

The Dewey Arch was something else. New York City, which does hoopla like none other, went all out, and in 1899 constructed a mammoth arch in Madison Square (23rd Street and Broadway). The finest architects were summoned to design it and build it for Dewey’s Triumphal Parade. Private funds were quickly raised. But the arch was temporary, constructed of plaster-over-wood material, as was common for World’s Fair Exhibitions. Covering it with concrete was to be forthcoming. Once the balance of the money was raised.

And if all the unexpected pomp and glory was not enough, the 60-year-old Admiral fell in love. He had been a widower for more than a quarter century. His much-younger bride, Mildred McLean Hazen, had been widowed for a decade as well.

The Siren Call of Politics

It came as no surprise that Admiral Dewey was wooed toward political office, specifically the Presidency. Republican President McKinley was very popular with no challengers. The Democrats, however, had a large segment that was unhappy with their apparent candidate, the populist William Jennings Bryan, who lost heavily in 1896 and wanted a rematch. The Admiral (non-political though he was) might pose a serious alternative.

After all, there have been men throughout the centuries who made the military-political transition easily. And successfully.

Admiral Dewey said no. He said no several times, acknowledging his complete lack of political qualifications. And interest. He had never even voted in an election. But Democratic bigwigs, desperate for a conservative alternative to Bryan, persisted. Finally, George Dewey agreed to explore his options.

A Foot-in-Mouth Candidate in 1900

Right out of the block, there was an “oops” moment. The Admiral stated publicly that he expected the job of president to be easy, since he would merely follow the laws enacted by the legislative body and “execute the laws of Congress as faithfully as I have always executed the orders of my superiors.”

Then of course, there was the personal “problem.” Mildred Hazen, the glamorous new Mrs. Dewey, was not only a wealthy socialite, but a Catholic. Many Americans still believed that the Pope would be whispering in the Admiral’s ear. But Dewey’s biggest problem was that he had deeded his new $50,000 mansion (the gift of a grateful nation) over to his new bride.

Candidate Dewey withdrew from politics, and returned to the world he knew much better. The Navy.

And Ever After

The Dewey Arch lasted only a few months before it began to decompose waiting for reasons and money to cover it in concrete. It was torn down.

In 1903, George Dewey was promoted by Act of Congress, to the special rank of Admiral of the Navy, retroactive to 1899. He was and still is the highest ranking Admiral in the USA.

He returned to active duties at the War Department, and served unstintingly for the rest of his life, adding his strong support to the newest technologies, i.e. submarines and naval aviation.

He died at 80, in 1918, and is buried in the Washington Cathedral.

Sources:

Sullivan, Mark – Our Times: The Turn of the Century – Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1927

Traxel, David – 1898: The Tumultuous Year of Victory, Invention, Internal Strife, and Industrial Expansion That Saw the Birth of the American Century – Alfred Knopf, 1998

https://www.politico.com/story/2015/12/admiral-george-dewey-born-dec-26-1837-217104

Pingback: Admiral George Dewey: The Boom and the Bust | Presidential History Blog | Vermont Folk Troth