During the past few decades, a couple of mild kerfluffles were posed by eminent scholars who suspected that POTUS Rough and Ready may have been done in!

Ol’ Zach

Zachary Taylor (1784-1850) was Virginia born to a middle class family who moved to Louisville, Kentucky when the future president was still a youngster. He received a moderate education, and by 20, decided to make the army his career. He rose in the ranks, and was considered a good officer.

He married Margaret Mackall Smith, originally from Maryland, when he was 23, and the young couple began a life on the move. They traveled from pillar to army-post, living in barracks, forts, tents, cabins, and wherever the army put them. Major, and later Colonel Taylor was said to be able to sleep in the saddle. In the expected time, the couple raised four children to maturity. Two died in infancy. It was a hard life.

During his decades in the regular army, which included service in the War of 1812, Taylor managed to put by enough money to purchase a plantation in Louisiana, and planned to make it their “retirement” home. It may have been a hard life, but it was a decent one.

Older Zach

Army officers are expected to be non-political, obeying orders from whoever is Commander-in-Chief at the time. Taylor was no exception. He took little interest in politics, never voted, and was never known to express any notable opinions, even if pressed.

He had also acquired his “Ol’ Rough and Ready” nickname, since he was the antithesis of the spit-and-polish image of a military general, like his counterpart, the towering Winfield Scott. At average size, perhaps 5’8, his boots were seldom shined, his clothes were whatever he pulled from the saddlebag, and the general impression was disheveled. Strangers meeting him had no clue that he was a senior army officer.

When the War with Mexico became a pending crisis in 1846-7, Taylor was already a General serving in the “west”, not far from the disputed area in Texas poised to ignite hostilities. He was ordered to take his command to the border. He did, was victorious in several skirmishes, incidents and bona fide fame-and-name-making battles. With President James K. Polk, committed to a single term, and not wildly popular anyway, General Taylor was considered a viable political option.

Problem was, he wasn’t interested. He was non-political, believing as a good soldier, his loyalty was to his Commander-in-Chief, period. He had never shown the slightest inclinations for office.

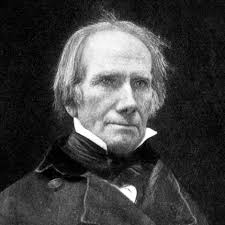

Henry Clay, Whig-Maker

In 1848, Henry Clay was not only the foremost Whig in the country, but at 71, had been on the national scene for nearly 40 years. But the Whig party had only existed for perhaps a decade, and they were still a motley group of assorted regional and fractious factions. Clay had already run for President three times – and lost. The last loss, in 1844, against the unknown dark horse Polk, was a total upset. That should have been his year – but Harry of the West blew it, so to speak.

Clay was not overly anxious to run again and lose – but neither was he anxious to throw serious support to another unknown. The one and only successful Whig election (in 1840) saw elderly ex-General William Henry Harrison win the presidency, but he died a month later. His in-name-only Whig VPOTUS, John Tyler, gave the Whigs nothing but agita.

Nevertheless, the political big-Whigs decided that another military hero could win and settled on Zachary Taylor, dangling whatever might seduce him away from his retirement in Louisiana. He offered a rare anomaly of being a Southerner and a slaveholder, but a staunch Unionist, strongly opposed to the extension of the “peculiar institution” in the territories. Perhaps against his better judgment, and surely against his (and Mrs. Taylor’s) personal inclinations, he relented, allowed others to do his campaigning, and won.

Agita….and Death

Zachary Taylor, 12th President, may not have been political by nature but he was an independent man, whose core philosophies were truly core: Presidents should not be involved in legislative matters, other than the constitutional veto power. Secession is abhorrent. Slavery should be contained where it was, and not expanded. Manifest Destiny (i.e. sea to shining sea) was perhaps a little too much.

Elder Statesman Senator Henry Clay, no huge fan of Taylor, was nearly 75 and in failing health, but began crafting a “compromise” bill of packaged-together diverse issues. He had done a similar service back in 1820 when slave-vs.-free states were an issue, alarming the Union even then.

Taylor threatened to veto the “Compromise of 1850” and some Congressional Whigs, in their own usual shambles of factions, even threatened Taylor’s impeachment.

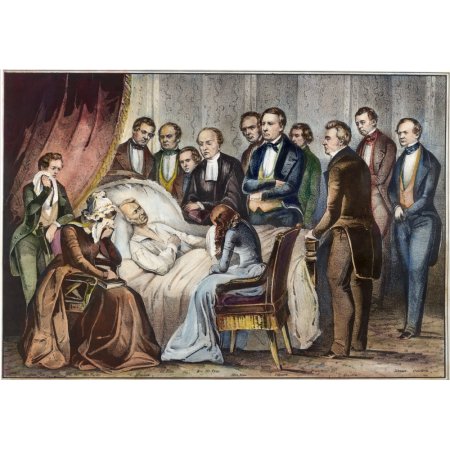

No one expected that Taylor would die in 1850. His health had been robust for a man of 65. The story goes that after a ceremony at the unfinished Washington Monument on a blistering July 4, he consumed a great amount of cherries and ice milk. Or ice water. (Milk wasn’t pasteurized, and Washington water was generally foul.) He became violently ill and died a few days later. The formal diagnosis (then) was cholera morbus, or (today) acute gastroenteritis. Even then, given the political situation, Taylor was a suspected victim of poisoning.

Under a more compliant President Millard Fillmore, The Compromise of 1850 passed, made nobody happy, caused seismic rifts, but delayed the Civil War by ten years.

150 Years Later

In 1991, some fine scholars arranged to have Taylor’s body exhumed for possible evidence of poison. They did find minute traces of arsenic, which most people have in their systems today, but not nearly enough to cause harm, let alone death. Some intrepid scholars still persist, seeking more evidence, but the Taylor descendants have declined further investigation, preferring to let Ol’ R and R RIP.

Sources:

Eisenhower, John S.D. – Zachary Taylor – Times Books, 2008

Hamilton, Holman – Zachary Taylor: Soldier in the White House – Bobbs-Merrill, 1951

Hoyt, Edwin P. – Zachary Taylor – Reilly and Lee, 1966

https:www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/presidents/zachary-taylor/

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Zachary-Taylor

https://www.senate.gov/senators/FeaturedBios/Featured_Bio_Clay.htm

Reblogged this on Dave Loves History.