In recent years, there has been a welcome addition to the world of history writing: narrative history, i.e. Making history “readable” without jeopardizing the factual.

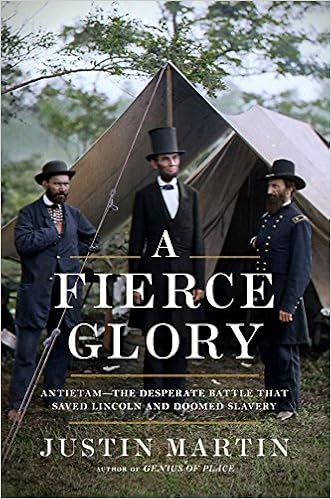

A Fierce Glory: Antietam – The Desperate Battle that Saved Lincoln and Doomed Slavery, by Justin Martin

Author Justin Martin has chosen to write A FIERCE GLORY: Antietam – The Desperate Battle that Saved Lincoln and Doomed Slavery, his eminently readable history of the Battle of Antietam as a “novel”. This in no way dilutes the thrust or importance of the battle, or the issues, or those intimately involved. It merely allows him some latitude in the telling.

The Battle of Sharpsburg, MD (South) or Antietam (North) took place on September 17, 1862, only weeks after the Second Battle of Bull Run, another debacle for the Union, and only two months following the withdrawal of the Union troops from the Virginia Peninsula, despite their overwhelming manpower.

Having relieved the arrogant General George McClellan-with-the-“slows” after the Peninsula Campaign, President Lincoln had appointed General John Pope, an incompetent braggart to conduct another debacle at Second Bull Run, relieved him, and once again reluctantly turned to McClellan. It had not been a good year for the Union, and a particularly bad one for Lincoln, still mourning for his 11-year-old son who died in February.

The thrust of the book, and indeed, what gives it its “soul,” is the interlocking, and sometimes contrapuntal strategies and goals of North, South, McClellan, Lee, and overwhelmingly, Lincoln. Martin argues that the generals were neither clueless nor accidentally engaged, as some historians have purported. They knew exactly what was going on, and for the most part, they knew why.

The South, having fought and won several battles, had recently appointed Robert E. Lee as its top commander. Their strategy was direct and ambitious. Fight and win a battle in the North (Maryland), continue North (Pennsylvania), hope foreign countries (England and France) will recognize them as the separate country they wanted to be, provide financial and perhaps military aid, and/or, at least insist upon becoming the brokers for a negotiated peace.

The Northern strategy was much simpler. “No.” Keep the South from “invading” the North; win battles (obviously not as easy as it sounded) and prevent foreign interference in any way.

Lincoln also had a card up his sleeve. As early as the Peninsula campaign, he began to consider the political and militarily strategic efficacy of emancipating the slaves in the South. England and France, who had banned slavery decades earlier, would never ally themselves with a slave holding country. But that too, was not as easy as it sounded. Most Union soldiers had signed on to save the Union, and cared little about freeing the slaves.

Lincoln had labored over that premise for several weeks, drafting and tweaking the essentials. He had brought it to his cabinet for discussion shortly after the Peninsula Campaign. All had agreed in concept and principle, but it was Secretary of State Seward who suggested that it not be made public until after a military victory, lest it appear as “a last ditch effort of the vanquished.” Lincoln thought the suggestion had merit, and waited.

Meanwhile, back to Maryland. Southerners had expected that South-ish Maryland would welcome the soldiers of Dixie. They were surprised that their welcome was cool at best.

Much has been written about the “lost” orders of General Lee being found by Union soldiers, wrapped around three cigars. Even more has been written about McClellan-with-the-slows reacting with his usual snail-like alacrity to this vital information. Martin barely mentions it.

Nevertheless, a huge battle ensues across several miles along the Antietam Creek, everyone fighting fiercely and bravely, with upwards of 14,000 casualties (North and South), making it the bloodiest one-day battle in US history. Both sides were now becoming inured to the long lists in the newspapers.

Author Martin is far more proficient at writing “personal” observations as opposed to battle scenes, thus calling it a novel serves him well. There are some nice vignettes. There are some nice anecdotes. He cannot avoid telling of the multiple attempts to cross a bridge by the hapless General Ambrose Burnside, but its description would be redundant, as he likely knows. He is much better telling about photographer Alexander Gardner, or Dr. Jonathan Letterman, two pioneering participants in the Civil War – or even Lincoln trudging wearily across the White House grounds to the War Office Telegraph Room. The reader can practically see the patience oozing out of Lincoln’s pores as he waits for clicking sounds over the wires to bring news of engagement, ground gained (or lost), and mostly casualties. McClellan was as sparing providing news as he was with providing victories.

So while the book uses Antietam as its centerpiece, it is essentially Antietam as its scenery. The book is all Lincoln and his overriding/underlying consideration of emancipation as a military strategy – and the secrecy of it, known only to a few.

Antietam was more of a “draw’ than a victory, according to most military historians. McClellan claimed it as a “great victory,” but then again, that was vintage McClellan. General Lee managed to keep most of his army intact and on the Virginia side of the Potomac so he could “invade” the North another day. But the waffling victory was better than the total losses that had preceded it, and it gave Lincoln the impetus to proclaim his intentions about emancipating the slaves, albeit with carefully crafted language to keep the border states from defecting and the overseas powers to remain overseas. It would take effect on January 1, 1863.

A Fierce Glory is a very nice read, especially for Civil War aficionados who want the people and don’t want the ponderous. I only wish Justin Martin had come up with a better title.

Martin, Justin – A FIERCE GLORY: Antietam – The Desperate Battle that Saved Lincoln and Doomed Slavery

DaCapo Press, 2018

ISBN: 978-0306825255

Hard Cover: $17.99