After the American Revolution ended, the State of Virginia wanted to honor its most renowned son with a commemorative statue.

Finding A Worthy Artist

Fine art and fine artists were a rarity in Colonial America, perhaps because people were more concerned with survival and earning a living than they were with fine accouterments. The earliest American artists of stature, John Singleton Copley and Benjamin West, began their careers in the US, but relocated to London, where their talents and skills would be better appreciated – at least financially.

Jean-Antoine Houdon was the most famous sculptor of his time in Europe. He had produced marble and bronze busts of Jefferson, Franklin and Voltaire.

But Virginia, in the process of building a State House in its new capital in Richmond, wanted to honor General Washington with a statue. There was no prestigious sculptor in America in 1782, so they asked Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, representing the new country in Europe, if they could make appropriate recommendations.

It was Thomas Jefferson who suggested Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741-1828), one of the foremost sculptors on the continent, and who had already created busts of Jefferson, Franklin and Voltaire. The Virginia legislature was amenable, and likewise commissioned Philadelphian Charles Willson Peale, the foremost artist in America, to paint a full length portrait of the famous general.

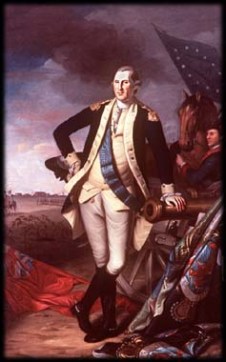

One of many full length portraits done by Charles Willson Peale, one of America’s prominent painters, in order for the sculptor to have proper reference materials of Franklin and Jefferson himself.

Houdon was eager to sculpt George Washington, France’s ally and successful hero. But he insisted that even the finest painted portrait would not be sufficient enough a likeness for his work. He insisted that he must travel to America and undertake Washington’s exact measurements personally.

Houdon Visits Mount Vernon

The State of Virginia agreed to commission the great French sculptor, including paying for (and insuring) his ocean voyage to and from America. George

Houdon visited Mt. Vernon for around two weeks. It took far longer to travel back and forth across the ocean.

Washington also agreed, and was pleased to extend the hospitality of his estate at Mount Vernon.

Houdon came with his assistants, his notebooks and casting materials, his measuring tapes and whatever other tools he required. Washington made time and allowed the artist to measure every inch from the length of his nose to the circumference of his fingers. Then Houdon made a plaster mask of the General’s face, by having Washington lay still for several hours with a plaster concoction on his face. He inserted hollow straws in Washington’s nostrils so he could breathe. The plaster face-mask would go back to Paris with Houdon. So would the terra cotta bust the sculptor made of the General.

The life-mask of George Washington was made at Mt. Vernon. Houdon took it back to Paris to replicate.

Discussions then ranged about “how” this life size sculpture would be presented. It had been fashionable for centuries to garb the honorees in classical style – togas or Biblical robes, or the armor plate of a thousand years before. Houdon wished to portray the General as he truly was, garbed in the clothing of his own time. It was a revolutionary idea – suited to the hero of the Revolution, who preferred that image as well.

The Classical and the Timeless

Houdon’s decision to present a “modern” Washington in his own clothing was accepted, but the sculptor was still deeply entrenched in the classical style adorned with the symbolism of art. He needed to present the “Cincinnatus” Washington. The civilian who took up arms for his country, became a hero, and then returned to his civilian life. A balance of war and peace. The accoutrements of the sculpture were not only accepted as essential, but they would also tell the story.

Washington is clothed in his uniform, but carries a civilian walking stick. He rests his hand on a bundle of rods, the Roman symbol of civilian authority. Of course there were thirteen rods in the bundle, symbolic of the thirteen States. The symbolic arrows are still reasons for conjecture, although some historians believe it represented the “wildness” of America. His farmer’s plow and his sword are behind him.

It would take the better part of five years for the life-sized sculpture to be completed, carved from fine Carrera marble, and exactly to the measurements Houdon made of his subject. The statue itself stands six-foot-two-and-a-half inches, including the half-inch for the heel of Washington’s boots. It also stands upon a Houdon-produced pedestal which gives heroic height to the image.

It was delivered to the State of Virginia in pieces, where it was assembled somewhere around 1791, and placed in the Rotunda of the Virginia State House in Richmond, where it remains today.

Emulating the Original

There is never any assurance against Mother Nature, and the Virginia Legislature was understandably concerned that fire, or damage to the rotunda roof might also destroy the statue. They commissioned bronze reproductions to be cast of the original, in case of any permanent damage. Between 1840 and 1910, additional casts were made, and today there are 33 life size reproductions housed at various locations across the country, notably in New York City, the University of Virginia, and the Art Institute of Chicago.

But the original, the one sculpted by Jean-Antoine Houdon himself, exactly measured from life and still considered by those who knew him, the most accurate likeness of George Washington, still stands in its original location: in the Rotunda of the Virginia State House in Richmond.

Sources:

http://www.britannica.com/biography/Jean-Antoine-Houdon

http://www.mountvernon.org/digital-encyclopedia/article/jean-antoine-houdon/

Cunliffe, Marcus – George Washington: Man and Monument – Little, Brown, 1958

Fascinating! And a much better tribute than, say, Horatio Greenough’s Zeus-like sculpture.

I was awed when I stood before Houdon’s GW statue. Looks like Houdon gave GW a slight paunch..a touch of reality.Feather, you did a great job telling the backstory of the statue.

Interesting. sd

Reblogged this on Lenora's Culture Center and Foray into History.

Thanks! Fascinating! So, given the tricky word “including,” how tall did Houdon say George Washington was without his boots? Six feet 2 inches? I’d like to reflect this in the next update to my book “George Washington’s Liberty Key, a best-seller at Mount Vernon: http://www.LibertyKey.US

WBAHR, your question is a good one. There seem to be many people, many who are Mount Vernon tour guides, who are “invested” with the claim that George Washington was 6 feet 2 inches, and some even say 6 feet 4 inches. The wording in this article is suggestive, yet vague on facts as to the precise measurements taken by Houdon. Where is a notebook by Houdon that records 6 feet 2 inches? As a scholar on George Washington, I came to question the “accepted narrative” because in the George Washington Parke Custis book on Washington, the larger than life “father of His country”, and surrogate father of GWPC, is described as “a shade over 6 feet.” OK, what is a “shade”? Four inches? Not likely. Two inches? Still not likely. More like a half an inch or a quarter of an inch. Then there is the measurement of Dr. James Craik on the death bed, who said Six feet. Then again, another doctor the next day wrote in his notebook, 6 feet 3 and a half inches. So Washington grew 3 and a half inches after he died. Not likely. I learned from talking with an undertaker that 6 feet 3 and a half inches is a measurement of a “standard size” casket, so likely the doctor was “ordering” the proper casket. Yet finally, in 1999, when I was on the Mount Vernon Board of Visitors, I was invited to a special reception of an exhibit at the Virginia Museum of History in Richmond that had a double exhibit on Washington. There I saw a letter from George Washington to his tailor in London in April 1763, when Washington was 31 years old, so not yet “shrinking” in height as older men sometimes do, and Washington wrote (as best I remember) “Prepare me a suit of clothes for a man of my height, to wit, six feet…” So while I consider Washington’s “adopted son” “Washy” a good source, and his personal doctor, Dr. James Craik, who measured Washington on his deathbed, an even better source, I say that George Washington himself is an unimpeachable source. — James Renwick Manship, aka Second to None George Washington Living Historian, PresidentWashington@me.com

https://secondtononewashington.blogspot.com/

JMANSHIP: Thanks for your comments! I also recall reading a story about the London tailor and the six feet measurement. I believe I also remember the story ended with something like, “…and Washington always had to alter his new clothes because they arrived too small.” I don’t know where Houdon’s notebook is; however, he has a reputation for exactness. I am guessing that the article’s statement of “exactly to the measurements Houdon made of his subject. The statue itself stands six-foot-two-and-a-half inches, including the half-inch for the heel of Washington’s boots.” means that Washington is supposed to be standing at six feet two inches (statue height minus a half-inch for shoes). However, Gouverneur Morris, who strongly resembled Washington and whose torso Houdon is said to have used for the statue, is, as you can see, not standing straight. I would imagine that if the body were standing straight, it might add at least another half to 3/4 inch to Washington’s height. 4WIW, my book, taking a number of measurements into account, currently has Washington at 6 feet 2 and 3/4 inches (not quite six foot three). Still, Washington was not the six feet 4, as Admiral de Grasse (he who called Washington “My little general!”) was reputed to be. Regardless, I appreciate your comments and the link to your book, which I just ordered on Amazon. Thanks again! http://www.LibertyKey.US